Penned By Boeard Member Ms. Alo Pal

My grandmother, to me, was an ocean of unconditional love—the best cook in the universe—who fed a joint family of ten, day in and day out, for decades. I hardly ever saw her cook. Food was on the table—several dishes—catering to the fancies and needs of every child and grandchild, on the dot, when we got back from school. Laundry got done, fresh linen was changed every week, flowers adorned every room, photo frames covered the walls, and cupboards were filled with her fascination for dolls. A succession of white rabbits as pets, parakeets, lovebirds, and a verandah full of flourishing flower pots added to the charm of our home.

The whole day saw a stream of friends and acquaintances walk into the house, and she would serve them tea and snacks. After lunch, a procession of beggars, rickshaw pullers, and hawkers would climb the stairs, and she would serve them all food.

In the late afternoons, after most of her day’s work was done, she would bathe and wear magnificent silk sarees at home for the rest of the day. When postcards from my grandfather arrived, she would put on her glasses and read them. When she needed something fixed in the house, she would write my father a note in impeccable Bangla script. When we children were being uncontrollably noisy and wild, she would write down the Bangla alphabet on pages and make us copy them—teaching us the direction in which our pencils were supposed to draw the lines.

It never occurred to me then that, by the time she was an adolescent, she had been married and had left her paternal home, or that she and her five sisters had all gone to school and were literate. You see, as I’ve stated earlier, my connection with her had little to do with her ability to read and write. And yet, that education gave her enormous autonomy and self-esteem. I realized that years later.

It may be a generalization in some pockets, but girls have it so much better in our country today. Few sights give me more joy than watching girls, their long hair neatly braided with ribbons, in their crisp uniforms, setting out for school. At Sharana too, in 25 years, it isn’t so much about sending the girl child to school anymore as it is about assisting them in carving out a career for themselves through education. Not everyone needs to be a graduate, but the greater the school education, the better the prospects for skilling.

But what of their mothers and grandmothers—ladies whose evidence of childhood and adolescence is marked only by the creases on their faces, recording the passage of time? Should the vast universe and power of the written word be denied to them? Can’t we, in the India of 2025, give them the privilege of literacy that my grandmother received over a hundred years ago?

This is exactly what Viji is doing with the ladies of Angalakuppam village under our literacy program for women.

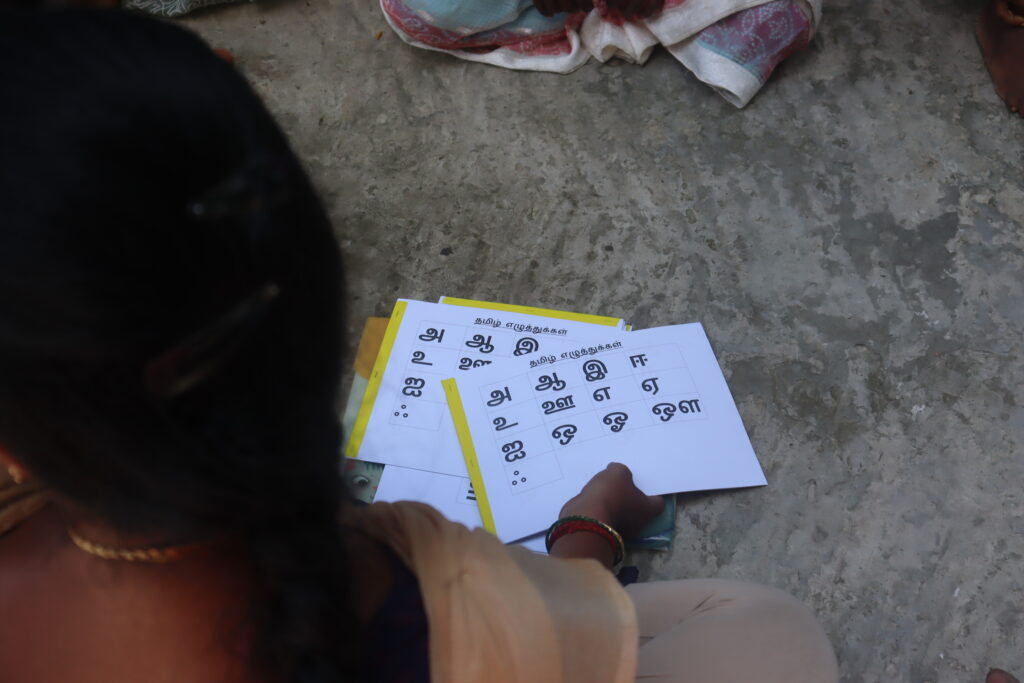

Our social worker, Ms. Vijji, goes to the 100 Days Work site to teach the women during their break.

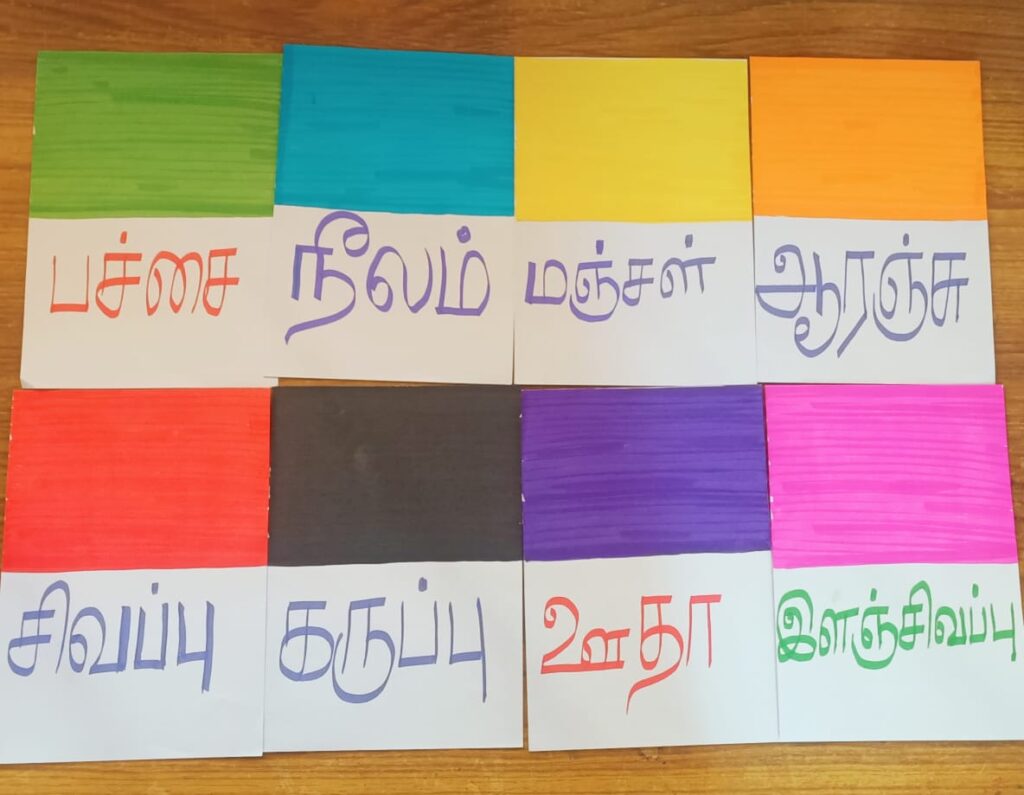

Our social workers use educational cards as a teaching tool for the women

Tamil Alphabets

Women learning how to write